Just over a year ago, research by Oxfam calculated that the eight richest men in the world hold the same amount of wealth as the bottom half of the world’s population, some 3.5 billion people. The wealth of the eight men is ‘biblical’ declared Gawain Kripke, Oxfam’s Director of policy and research. “Left unchecked, growing inequality threatens to pull our societies apart.”

There is no doubt that the rich are getting richer, largely because we now live in an age where technologies and money can be flashed around the world at the blink of an eye.

It’s hard to know what can be done about the inequality. The global giants neatly side-step any punitive tax demands. If labour costs are too high, then products are manufactured in a location with cheaper workers. Countries prostrate themselves to attract an Apple HQ or a new Amazon distribution hub, offering incentives and tax-breaks. Rather than revolt against these over-bearing giants, nations beg the companies to choose them.

Sadly, it sometimes seems that the only hope for fairer distribution is for the super-rich to be benevolent and share their wealth. Begging for charity is not a palatable option in the 21st Century.

But if we do have to resort to philanthropy, then we could do with more people like Bill Gates, who in purely monetary terms is probably the most generous man in the world, with only Warren Buffet able to contest the claim.

Gates has famously stated that, “Money has no utility to me beyond a certain point. Its utility is entirely in building an organisation and getting the resources out to the poorest in the world.”

With his wife Melinda, Bill founded and chairs the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the world’s largest private charitable foundation, which works to save lives and improve global health, and is working with Rotary International to eliminate polio.

According to www.wealthx.com, the foundation has given more than $36 billion in grant payments to various philanthropic causes. Recipients include GAVI Alliance, World Health Organisation, The Rotary Foundation, The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, Malaria, Nasscom Foundation, and UNICEF.

Gates has sold or given away so much of his stake in Microsoft that he now owns little over 1% of shares. In 2010 Gates and Warren Buffett created the Giving Pledge, a promise to give at least half of their wealth to charity, and called on other billionaires to join them. More than 170 of the world’s richest people, including Mark Zuckerberg, Michael Bloomberg and George Lucas, have so far signed up.

Gates said the pledge was “about building on a wonderful tradition of philanthropy that will ultimately help the world become a much better place.”

Gates the Good Guy

A quick web search uncovers multiple examples of the extensive philanthropy from Bill and his wife Melinda, but with untold billions in the bank it’s not exactly a heavy sacrifice for the pair. But you also uncover something else. Gates is just as generous with his time as his money. This is a man truly driven to change the world, and he is increasingly being regarded as a decent human being who is doing his best.

A simple test of this theory is to delve a bit deeper into web forums and responses to newspaper features, where people are never afraid to vent their spleen, spew conspiracy theories and curse the rich and famous. Inevitably, I found the angry outbursts of the inequity of modern society, yet what was striking was the volume of personal testaments to his passion to make a difference.

This entry on a Q&A site from Venkatraman Vaitheeswaran was far from untypical: “Bill Gates came on a surprise visit to a brothel area in Pune, India and was lecturing the commercial sex workers there on the importance of protection and HIV awareness. Local politicians and the Indian media had no idea of his visit until he was on his way back to Mumbai. That’s humility. No tantrums. No photo-ops.

“As well as giving lots of his money, Bill Gates gives a lot of his time, a commodity of which he has only the same allowance as everybody else.”

All-round good-guy? It would have been hard to imagine a decade ago, when he was regarded as the impatient and controlling boss of one of the world’s most disliked mega-brands.

The Early Days

Gates was born in Seattle on October 28th, 1955 and was known as William Gates III or “Trey”. The family were known for their competitive spirit. One friend was quoted as saying, “It didn’t matter whether it was hearts or pickle ball or swimming to the dock ... there was always a reward for winning and there was always a penalty for losing.”

When he was 13, his school used the takings from a jumble sale to buy a Teletype Model 33 ASR terminal and a block of computer time on a General Electric (GE) computer for the school’s students. Gates took an interest in programming the GE system in BASIC, and was excused from math classes to pursue his interest. He wrote his first computer program on this machine, which was a version of noughts and crosses played against the computer. Gates was fascinated by the machine and how it would always execute software code perfectly.

It wasn’t long before the allotted time on the computer was exhausted so Gates and three friends found way to hack into the computers at a local computer company to access free time. They were caught and banned for using the computers at the Computer Center Corporation (CCC) for a whole summer. At the end of the ban, the four students offered to find bugs in CCC’s software in exchange for extra computer time. They were so successful that another local company, Information Sciences Inc. hired the four students to write a payroll programme in COBOL, providing them computer time and royalties. Gates then wrote the school’s computer programme to schedule students in classes. He modified the code to ensure the girls he wanted to be with were in his class.

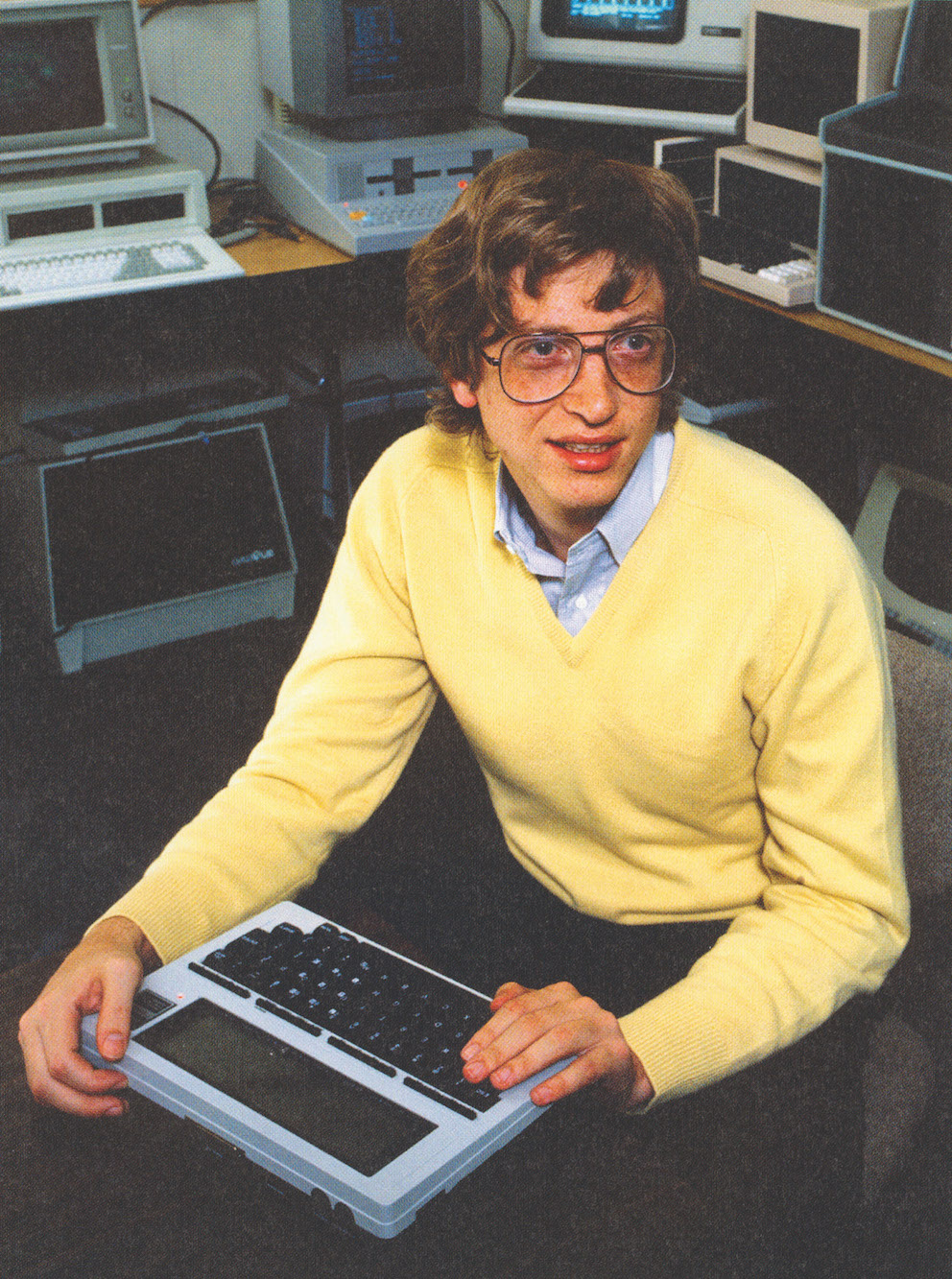

Gates graduated to Harvard but he remained in touch with Paul Allen, one of his fellow hackers and worked with him at Honeywell during the summer of 1974.

In 1975 a new computer was launched called the MITS Altair 8800 and the pair decided they wanted to write software for this new piece of kit. In order to start their new company, Gates dropped out of Harvard and they contacted the manufacturer, Micro Instrumentation and Telemetry Systems (MITS) and hoodwinked MITS into believing they were working on a BASIC interpreter for the platform. The pitch succeeded and they quickly set to work to make their claim come true. They set up a company called Micro-Soft, but before long it became simply Microsoft.

Gates soon learnt the value of his work but also had an early knack of upsetting the computer fraternity. As successful as Microsoft was, it always had its enemies, and was often prone to malicious hacking attacks. Wikipedia notes his early scrapes: “Microsoft’s Altair BASIC was popular with computer hobbyists, but Gates discovered that a pre-market copy had leaked into the community and was being widely copied and distributed. In February 1976, Gates wrote an Open Letter to Hobbyists in the MITS newsletter in which he asserted that more than 90% of the users of Microsoft Altair BASIC had not paid Microsoft for it and by doing so the Altair “hobby market” was in danger of eliminating the incentive for any professional developers to produce, distribute, and maintain high-quality software. This letter was unpopular with many computer hobbyists, but Gates persisted in his belief that software developers should be able to demand payment.”

The rise and rise of Microsoft

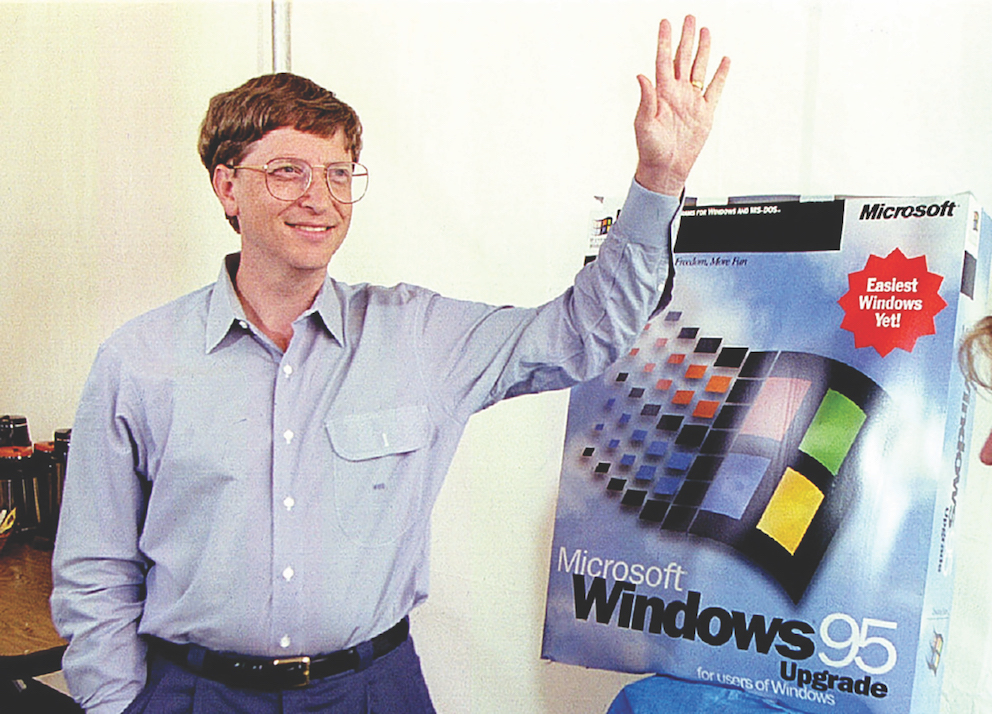

If he was alienating some of the hobbyists, he was also gaining some more welcome attention, and in 1980 Gates and Allen were approached by IBM who were looking for assistance with their new personal computer, the IBM PC. In the end Microsoft delivered a whole operating system, PC DOS, retaining the copyright and in the process making a name for themselves across the globe. The computer press soon caught on to the fact that Gates was the main player, with PC magazine declaring him ‘The man behind the machine’. Microsoft’s ascendancy to a world power was complete in 1985 when it released to the market an exciting new product called Windows. It was, apparently, rather popular.

His operating systems and software revolutionised computing and made access to a computer more accessible than anyone could have dreamed. Talking to The Telegraph in 2008, Gates recalled, “When Paul Allen and I started Microsoft over 30 years ago, we had big dreams about software. We had dreams about the impact it could have. We talked about a computer on every desk and in every home. It’s been amazing to see so much of that dream become a reality and touch so many lives. I never imagined what an incredible and important company would spring from those original ideas.”

The value of Microsoft peaked when the share price hit $119.94 in December 1999. With 5,160,024,593 outstanding shares, it had a market capitalisation of $618.9 billion.

Why Microsoft was so unloved

An innovator like Gates should have been lauded for his achievements and contribution to society, but for every fan there was a detractor. Rather than look up to Microsoft, many saw a corporate bully.

In 1998 he was summoned to court to answer for Microsoft’s restrictive business practices. In the U.S. antitrust law (competition law is the UK equivalent) case, United States v. Microsoft Corporation, Microsoft was accused of abusing its monopoly on Intel-based personal computers. Central to the case was whether Microsoft was allowed to bundle its flagship Internet Explorer web browser software with its Microsoft Windows operating system, thus prompting all PC users to access the internet via Microsoft’s web browsing software.

Judge Thomas Penfield Jackson found that Microsoft’s dominance of the market constituted a monopoly, and that Microsoft had taken actions to crush threats to that monopoly. The court ordered a breakup of Microsoft into two separate units, one to produce the operating system, and one to produce other software components.

On appeal, the break-up was overruled and the sanctions were watered down significantly, but the reputational damage was done. Microsoft was the corporate behemoth that everyone loved to hate. In contrast, the world loved Apple, the plucky and crucially, cool, underdog.

It was the loss of cool, which really did for Microsoft. In 2012, Vanity Fair noted that since 2000 the company had fallen flat in every area it entered: e-books, music, search, social networking - and the blame was firmly laid at a demoralising management culture. Author Kurt Eichenwald’s interviews with employees revealed that a management system known as “stack ranking” - a programme that forced every unit to declare a certain percentage of employees as top performers, good performers, average, and poor - effectively crippled Microsoft’s ability to innovate. “Every current and former Microsoft employee I interviewed—every one—cited stack ranking as the most destructive process inside of Microsoft, something that drove out untold numbers of employees.”

One developer told Eichenwald: “If you were in a team of ten people, you walked in the first day knowing that, no matter how good everyone was, two people were going to get a great review, seven were going to get mediocre reviews, and one was going to get a terrible review. It leads to employees focusing on competing with each other rather than competing with other companies.”

An anonymous former Microsoft senior marketing manager concluded: “I see Microsoft as technology’s answer to Sears. In the 40s, 50s, and 60s, Sears had it nailed. It was top-notch, but now it’s just a barren wasteland. And that’s Microsoft. The company just isn’t cool anymore.”

It took a long time but Microsoft finally shrugged off the criticisms. Today it sits on the side looking on as Apple is accused of over-pricing, Amazon is blamed for the death of the High Street and the finger is pointed at the mis-use of personal data on Facebook.

How the geek became cool

Maybe Bill’s transformation can be credited to Melinda. The pair met in 1987, four months into her job at Microsoft, when they sat next to each other at an Expo trade-fair dinner in New York. “He was funnier than I expected him to be,” she reported.

In a profile of the power couple, The Independent wrote, “Whatever first attracted Ms. French to Bill Gates, he was struck by her forthrightness and independence. It was she who first spurred him into impulses of charity. After their engagement in 1993, during Melinda’s wedding shower, her mother Mary, suffering from breast cancer, read her an admonitory letter whose gist was, “from those to whom much is given, much is expected”. Mary died months later, but her advice provoked the William H Gates Foundation. Run by Bill’s father, its aim was to put laptops in every classroom. Then the couple decided that the most pressing issue in the US was reforming the education system.

“Then, after their wedding in Hawaii (on New Year’s Day 1994) Melinda read in The New York Times about the millions of children in developing countries dying of malaria and TB. She made world poverty their priority concern.”

At first Melinda was the driving force of the Foundation, but once Bill departed from his day-to-day role at Microsoft, he threw himself wholeheartedly into the charitable work.

In 2005 Time magazine named Bill Gates and Melinda, along with Bono, as the Persons of the Year citing three people on a global mission to end poverty, disease — and indifference. Bono said at the time, “Lots of people like Bill – and I include myself – are enraged and we sweep ourselves into a fury at the wanton loss of lives. We need a much slower pulse to help us to be rational. Melinda is that pulse.”

Melinda is quick to share the praise with her husband, highlighting his open-mindedness and compassion. She wrote “As I’ve thought more deeply about equality for women around the world, I’ve been proud that Bill and I have achieved it in our life together. This is a balance that married couples, and co-workers, all over the world are always trying to strike.”

Bill’s journey from corporate suit to poverty campaigner owes much to the relationship with his wife, but there was another key influence. Gates was struck by the words of the pioneering American philanthropist, Andrew Carnegie.

Carnegie’s statement should be a mantra for everyone who find themselves in a position of having more money than they can possibly spend:

“No man can become rich without himself enriching others. The man who dies rich dies disgraced.”