Imran Khan, the Oxford-educated former playboy cricketer, is roaring along the Pakistani campaign trail in his armoured car. Horns honk. Crowds yell. Super-fans on motorbikes race after him. Thousands line the road with his flags. Hysteria grips the small Punjabi city of Mandi Bahauddin. Khan, however, is miles away. “British politics,” he intones. “It’s such boring politics. If I had to be in British politics, after two months I would just … commit suicide.”

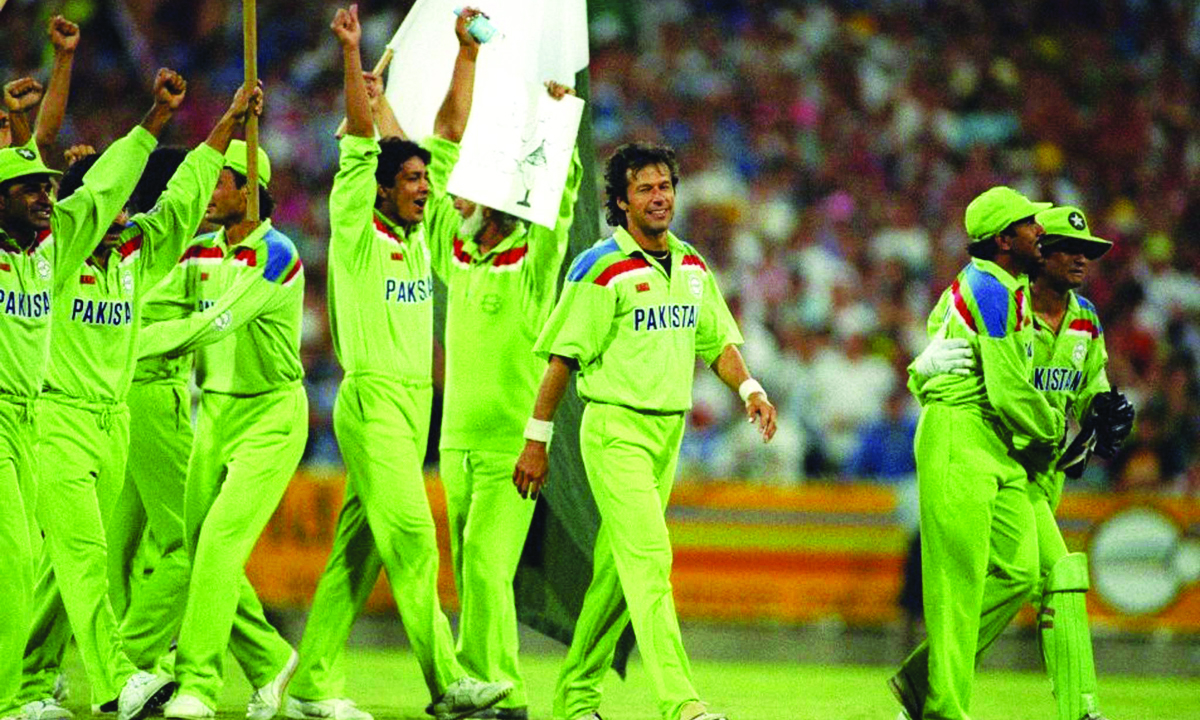

Imran Khan is the former international cricket star who has promised a “new Pakistan” and an end to corruption after claiming victory in the 2018 general election. The charismatic captain who led Pakistan to a World Cup victory in 1992, and played for Sussex from 1983 - 88, has long shed his celebrity playboy image and now styles himself as a pious, populist, anti-poverty reformer.

Mr Khan, 65, struggled for years to turn popular support into electoral gains. He launched his Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) in 1996 but he was the only candidate in the party to win a seat in 2002. The PTI boycotted the 2008 vote.

Although he has long been one of Pakistan’s best-known faces internationally, he spent years on the political sidelines. That led to teasing - for some Imran Khan became “Imran Khan’t”. It took until the last general election in 2013 for his party to emerge as a serious player, when it narrowly missed becoming the second largest party nationally.

But five years on, he has won an election in Pakistan, a nuclear-armed Islamic republic and a potential flashpoint because of its rocky relations with India and Afghanistan. During the campaign, Mr Khan faced accusations, which he denied, that he was the military’s favoured candidate and that its intelligence service was working behind the scenes against his key rivals. He needed an electoral swing of epic proportions to finally bring his political dreams to fruition.

Oxford-educated Mr Khan had an illustrious career in international cricket spanning two decades from the 1970s. He also developed a reputation as something of a playboy on the London nightclub circuit, though he denies that he ever drank alcohol or engaged in any activities that may be considered inappropriate for a conservative Pakistani Muslim.

Many say his subsequent forays into the fields of philanthropy and politics were fuelled by a desire to put to use the leadership qualities and goodwill he acquired as a cricketer.

His pin-up looks and private life have ensured he’s been a favourite of the world’s media for decades. Of course, it didn’t hurt his chances in every direction when in 1995, the 43-year-old married heiress Jemima Goldsmith, the daughter of one of the world’s richest men, Sir James Goldsmith. The marriage produced two boys but was dissolved in 2004.

A second marriage in 2015, to journalist Reham Khan, lasted less than a year. The former BBC weather presenter alleges she was bullied by his supporters and has written a tell-all memoir. It has been making waves in Pakistan, where its publication was, conveniently, put on hold by the courts in the run-up to the election.

Mr Khan wed again in 2018 in a low-profile ceremony in Lahore. His third wife Bushra Watto, a mother of five, was described as his spiritual adviser, and observers say the match plays well with his public shows of devotion to Islam.

Khan’s route to power has been plagued by problems. He upholds liberalism but at the same time appeals to Islamic values and anti-West sentiment, especially when it comes to perceived interference in Pakistan’s internal affairs. He campaigned vocally against US drone strikes against militants in Pakistan’s tribal areas as part of the “war on terror”.

He has criticised some of the Taliban’s violence but last year his party’s government in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province gave $3m (£2.3m) to the notorious Haqqania madrassa. Its head, Maulana Sami-ul Haq, is known as the “father of the Taliban”. Khan has had to fight off taunts he should be called “Taliban Khan”.

But it’s his campaign against corruption and dynastic politics in Pakistan, and a promise to raise a whole new class of “clean” politicians, that seems to have chimed with his supporters.

He has sought to ride a wave of disillusionment at Pakistan’s old political order, particularly among the urban middle class and young voters, who are tired of living in a country with an economy and currency on the slide, and water and power supplies in constant crisis. The main target of his anti-corruption campaign has been his arch-rival Nawaz Sharif. The Panama Papers leak in 2015 revealed several of Mr Sharif’s children had links to offshore companies which were allegedly used to channel funds and buy foreign assets.

That moment provided Imran Khan with his big chance - and he seized it. His campaign against the Sharifs saw him threaten to blockade the capital with his supporters. Nawaz Sharif was ousted from the office of prime minister in 2017 and is now behind bars, sentenced to 10 years in prison by an anti-corruption court. The Sharifs maintain the charges are politically motivated.

With his main rival down but not out, Khan redoubled his efforts to woo politicians with dependable votes to his camp. Critics say many of the so-called “electables” were coerced into defecting, charges the military and PTI deny.

Mr Khan has rejected persistent claims that the powerful military manipulated the poll in support of his campaign. He told the BBC in May: “The current military chief, General Bajwa, is probably the most pro-democratic man we have ever seen.” How he might get on with the military in the longer term remains an open question.

If he really wants to tackle some of Pakistan’s root problems, he may find himself on a collision course with the establishment, as previous governments have discovered.

Imran Khan was born in 1952 in Lahore, Punjab and educated at Aitchison, Worcester and later at Keble College, Oxford. His first love was cricket which he started playing at the age of 13. After playing for Worcestershire Cricket Club, he made his debut for the Pakistan National Team during the 1971 series against England at Edgbaston. Whilst at Keble, he studied Philosophy, Politics and Economics, graduating with honours in 1975. This marks his interest in his current role from an early age with cricket being a fun side-line whilst waiting for the Pakistani political scene to move in his favour.

Khan admitted to a little ball tampering in his day. In 1994, Khan admitted that, during Test matches, he “occasionally scratched the side of the ball and lifted the seam.” He had also added, “Only once did I use an object. When Sussex were playing Hampshire in 1981 the ball was not deviating at all. I got the 12th man to bring out a bottle top and it started to move around a lot. In 1996, Khan successfully defended himself in a libel action brought forth by former English captain and all-rounder Ian Botham and batsman Allan Lamb over comments they alleged were made by Khan in two articles about the above-mentioned ball-tampering and another article published in an Indian magazine, India Today. They claimed that, in the latter publication, Khan had called the two cricketers “racist, ill-educated and lacking in class.” Khan protested that he had been misquoted, saying that he was defending himself after having admitted that he tampered with a ball in a county match 18 years ago. Khan won the libel case, which the judge labelled a “complete exercise in futility”, with a 10–2 majority decision by the jury.

Such ball tampering might stand him in good stead to be a politician as playing by the rules is not a phrase that troubles any of our global leaders and certainly not in the aggressive rough and tumble of Indian and Pakistani political circles. A number of opposition parties have alleged “massive rigging” in Khan’s favour amid allegations of military interference in the general elections. Nawaz Sharif and his PML-N party, in particular, claimed that a conspiracy between the judiciary and military had influenced the election in favour of Khan and PTI. The Election Commission of Pakistan, however, rejected allegations of rigging and Sharif and his PML-N later conceded victory to Khan, despite lingering ‘reservations’ regarding the result. Two days after the general elections were held, the chief observer of the European Union Election Observation Mission to Pakistan, Michael Gahler confirmed that the overall situation of the general election was satisfactory.

On March 18, 2012, Salman Rushdie critiqued Khan after Khan refused to attend the India Today Conference because of Rushdie’s attendance citing the “immeasurable hurt” that Rushdie’s writings have caused Muslims around the world. Rushdie, in turn, suggested Khan was a “dictator in waiting.” In 2011, while writing for The Washington Post, Richard Leiby termed Khan as an underdog adding that he “often sounds like a pro-democracy liberal but is well-known for his coziness with conservative Islamist parties.” Ayesha Siddiqa, in September 2014, writing for The Express Tribune, claimed that “while we can all sympathise with Khan’s right to change the political tone, it would be worthwhile for him to envision how he would, if he did become the prime minister of this country, put the genie back into the bottle.”

Declan Walsh in The Guardian newspaper in 2005 described Khan as a “miserable politician,” observing that, “Khan’s ideas and affiliations since entering politics in 1996 have swerved and skidded like a rickshaw in a rainshower... He preaches democracy one day but gives a vote to reactionary mullahs the next.” Khan has also been accused by some opponents and critics of hypocrisy and opportunism, including what has been called his life’s “playboy to puritan U-turn.” Political commentator Najam Sethi, stated that, “A lot of the Imran Khan story is about backtracking on a lot of things he said earlier, which is why this doesn’t inspire people.” Author Fatima Bhutto has criticised Khan for “incredible coziness not with the military but with dictatorship” as well as some of his political decisions.

It’s not hard to see why Imran Khan’s stunning victory in the Pakistan elections attracted global media coverage. The story of a cricketing hero and former playboy turned political superstar and scourge of the establishment that spawned him was too good to miss.

Given Pakistan’s history of army coups, Khan’s rise to power seemed like a modern parable foretelling the triumph of people’s democracy over the dark-suited, sunglassed forces of “deep state” military control, manipulation and repression.

Beguiling though this storyline is, it did not really happen that way. Indeed, Khan owed his success, in part at least, to the covert meddling of those same shadowy spooks and generals, according to EU poll monitors. Yet who governs Pakistan, and how, is still a matter of high international importance. Take female suffrage. Equal voting rights are absent in some Muslim countries. But Pakistan, where women comprise 44% of eligible voters, has made exceptional progress. Veiled female residents of conservative tribal areas such as South Waziristan made history last Wednesday when they cast votes for the first time.

Pakistan matters because, with its youthful population of more than 200 million (66% are under 30), it is a country of vast potential handicapped by endemic poverty, illiteracy and inequality. It is also, not coincidentally, a battleground pitting anti-western Islamists, schooled in international jihad in Saudi-funded madrassas, against the secular, anglophone elite. It is central to the “war on terror”. Its stability and security, or lack of it, has a potentially global impact. For the British, Pakistan exercises an abiding fascination, rooted in the Raj’s disastrous part in its bloody 1947 birth and in continuing, close ethnic and cultural ties. For the Americans, self-anointed heirs to empire, Pakistan plays the dual role of indispensable ally and duplicitous villain in their endless Afghan drama. For many in India, Islamabad is the nuclear-armed bogeyman next door. For expansionist China, Pakistan is a key link in its grandiose Belt and Road trading franchise, reliant on Beijing’s loans, investment and goodwill.

How the untested Khan, wholly lacking in governmental experience, will approach these complex issues and historical burdens is open to question. What is clear is that he has changed radically since his hell-raising West End days. Launching his Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) party, meaning “movement for justice”, in 1996, a newly earnest Khan, now 65, made doing God’s will and fighting corruption his main aims in life. “Far from being the Islamic welfare state that was envisaged, Pakistan is a country where politics is a game of loot and plunder,” Khan wrote in his memoir, Pakistan: A Personal History. His new party, he said, would strive to “end exploitation and ensure a society based on honesty, merit and integrity”.

Khan espoused a conservative religious outlook, favouring sharia law and controversially backing radical anti-blasphemy laws. His criticism of US drone strikes earned him the nickname “Taliban Khan”. And he rediscovered his family’s Afghan roots and Pashtun tribal identity. Coincidentally or not, this won him support among conservatives.

Likewise, courting populist opinion, Khan turned against Pakistan’s western-educated ruling class, despite graduating from Oxford university. Colonialism had wrought lasting damage across the subcontinent, he wrote, by destroying self-esteem. “The inferiority complex that is ingrained in a conquered nation results in its imitation of some of the worst aspects of the conquerors, while at the same time neglecting its own great traditions.”

Pakistan’s generals are accustomed to exercising sole control of foreign and security policy. Challenging them can be a career or even life-ending experience. So if Khan, for example, wants to break with the US, befriend India, or talk to terrorists, he had better watch his back. Whatever the popular storyline says about democracy redux, the hidden hand on the new prime minister’s shoulder is real. It will be hard to shake off.