Until February 13th 2020, the nation had little idea who Rishi Sunak was. As l write this on April 20th 2020, he is fast on his way to becoming a political rock star and tipped to be a future Prime Minster. So who is Rishi Sunak - or Dishy Rishi as many of the ladies are calling him?

Sunak was born in 1980 to a doctor father and pharmacist mother in Southampton. The child of first-generation immigrants, his parents came to the UK with his grandparents around 60 years ago from East Africa. He attended Winchester, the private all-boys boarding school in Hampshire with eye-watering yearly fees of £41,709, where he became head boy.

He quickly moved on to another exclusive institution by studying PPE (politics, philosophy and economics) – the degree of choice for aspiring politicians – at Oxford. It seems that Sunak was adept from a young age at navigating the predominantly white and upper-class establishments that historically thrust the country’s wealthiest into powerful positions.

Other Tory politicians of South Asian heritage have had noticeably less privileged routes into politics – Sajid Javid and Priti Patel both shunned Oxbridge and went to a comprehensive and a grammar school respectively.

The young Rishi, known as Rish to his friends, spoke English at home and grew up passionate about cricket, Southampton FC and its footballing genius, Matt Le Tissier. A practising Hindu, Sunak recalled: ‘I’d be at the temple at the weekend but I’d also be at the Saints game as well on a Saturday.” He was the target of occasional racism, mentioning to the BBC how it stung when he was abused as a Paki in a local fast food restaurant.

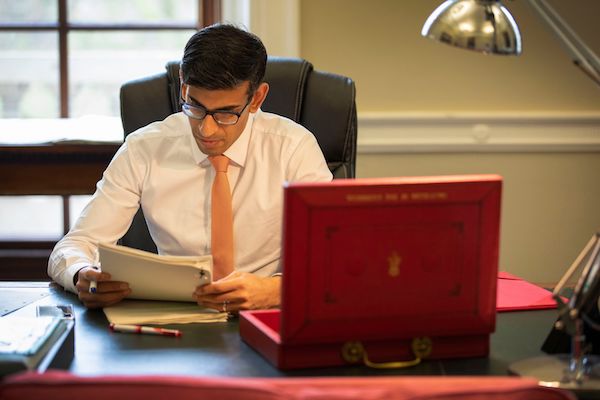

In many ways, Sunak is a cookie-cutter Conservative politician with the PPE degree to match. The main difference is he chose not to fawn over Thatcher with student Tories and became president of the Oxford University Investment Society. Sunak the undergraduate would have been thrilled to see his older self deliver his first budget only weeks into the job – something his predecessor Sajid Javid never got the chance to.

He is also a staunch Brexiteer which was a grave disappointment to David Cameron, who had tried personally to win over the newly elected MP. According to one individual with knowledge of the meeting, Cameron sighed as the implacable Sunak left the room: “If we’ve lost Rishi, we’ve lost the future of the party”. He is also rumoured to have bombshell views on the future of the United Kingdom.

One fellow Conservative recalls: “I remember discussing the future of the Union with Rishi and he argued that England should break away. He was advocating the end of the UK because it doesn’t make financial sense to him. He doesn’t have any love for the institution and I suspect he looks at it, as he looks at anything: what’s the profit?” Sunak’s allies say the chancellor does not recall the conversation and is a staunch supporter of the Union and the shared values it represents”.

Coronavirus has plunged the world economy into recession, but Sunak has already faced one global cataclysm: the 2008 financial crisis. Short- ly after graduating from Oxford, Sunak worked at Goldman Sachs as a junior analyst in the merchant banking division.

After studying for his MBA as a Ful- bright Scholar at Stanford, Sunak joined the Children’s Investment Fund Management, a London-based firm founded by billionaire Chris Hohn.

The controversial hedge fund made a name for itself as one of the most successful and aggressive hedge funds of the financial boom. In 2007, the company launched a campaign against the Dutch bank ABN Amro, leading to its purchase by the Royal Bank of Scot- land (RBS). A year later, the resulting debt led to the government handing RBS a whopping £45 billion bailout during the financial meltdown.

Sunak’s characterisation as the ‘down-to-earth Tory stumping up money to help the country get through coronavirus’ is ironic, mainly because of the extreme wealth in his own household.

At Stanford, he met and subsequently married Akshata Murthy, the daughter of a India’s 6th richest man, billionaire N.R Narayana Murthy who is the co-founder of Infosys, an IT company, and with whom he has two children, Krishna and Anoushka. The couple own at least four properties totalling £10 million across the UK and the US – including a five-bedroom home in London valued at £7 million alone. His wife’s stake in her father’s IT company is reportedly worth £185 million and she now runs her own fashion label, Akshata Designs.

When he left finance, Sunak decided to serve the community. After William Hague stood down in 2015 as Conservative MP for Richmond in North Yorkshire, Sunak took a gamble and ran as Hague’s successor. He bet right, and won, becoming the first MP of South Asian heritage for the constituency.

On Political Thinking, Sunak joked that his family represents the sum total of ethnic diversity in the area.

Becoming an MP marked the first step in a seamless political career, in which Sunak consistently chose right. Many politicians spend their entire lives attempting to become chancellor, but Sunak got there in five years.

He voted leave in the 2016 referendum, aligning himself with Johnson early on, and his only misdemeanour was joining Michael Gove’s leadership camp after David Cameron resigned.

He rectified this two years later, when Theresa May made her ignominious exit, and dutifully returned to Johnson.

It was a move that paid off: he was rewarded with a Cabinet position as Chief Treasury secretary under then-Chancellor Sajid Javid. He served under Javid, at one point calling him a “mentor” and a “good friend”.

Sunak’s career took an unexpectedly Shakespearean turn when Javid dramatically quit in February, though Sunak, the Star Wars fan who dreamed of being a Jedi knight as a child, might better describe this as his Darth Vader versus Obi-Wan moment.

Javid was famously given an ultimatum to keep his position on the condition he sacked all of his advisors. It was the culmination of months of tension between Johnson, his advisor Dominic Cummings, and Javid, in which Johnson and Cummings sought greater control over the Treasury, which traditionally operates separately to No.10. Javid later said that “no self-respecting minister” could accept those terms. Cue: Rishi Sunak, the minister who could.

“He’s young and a lot more amenable to what the government want to do,” says former Guardian columnist Dawn Foster.

She argues that Javid was a lot more experienced as a minister, meaning that he pushed back on government policy – something that is less of a threat with Sunak. “I think Boris need- ed to get some loyalists into the Cabinet and Rishi is young with no real backstory, and no real history. He’s perfect for the Treasury as they wanted someone to carry out exactly what Number 10 wanted.”

For all the claims of Sunak’s competence, there are flaws with his COVID-19 emergency measures. The five- week wait for Universal Credit is still in place, despite nearly a million people applying in just a fortnight. Despite the promised grants for self-employed workers, the Institute for Fiscal Studies reports that two million workers could be left out and unable to access help. The question is whether these are oversights or deliberate gaps in policy.

Reports from people who work with him is that “he reads everything that crosses his desk; he reads the details and he’s a pragmatic political”. The gaps in the package to support workers are not because of an ‘i’ he didn’t dot, or a ‘t’ he didn’t cross. It’s indicative of residual hawkishness of deficit reduction but never forget his true colours, which are deregulation, low tax and low public spending – it’s where his heart is.

He sounds like Gordon Brown at his best, taking decisive and dramatic action to meet the challenge of the financial crash. His approach was inclusive, consulting the Trades Union Congress as well as employers. Presumably, John McDonnell, the shadow chancellor, didn’t want to be consulted, and went on TV within minutes to complain that Sunak hadn’t gone far enough or fast enough.

This partisanship was in contrast with the reaction of Frances O’Grady, the TUC general secretary, who praised Sunak for showing “real leadership”. Even Len McCluskey, McDonnell’s co-ideologue, said the chancellor had “done the right thing.”

“He is smart, he’s energetic and he listens, which is important,” says O’Grady. She would not normally be a fan of a Tory chancellor, but several days of negotiating with Sunak over the coronavirus jobs package won her over: “It’s a lot of responsibility on young shoulders. What I would say is that he does have emotional intelligence. It’s a different style, without that sense of superiority that some have.

“He is quite frank in saying he never expected he would be in this position; this is not Conservatism as we have known it for 40 years. Things are happening really fast, judgments are being made fast.”

Carolyn Fairbairn, head of the CBI emloyers’ federation, also became an admirer over cups of tea at the Treasury: “We all just felt that incredible relief. He showed that you can come together and do things that are big and have the potential to change the course of the river.”

His briefing speeches have begun to hint at the fact that HMRC will work hard on getting this money back. On his April 18th daily briefing, he said that all of the money promised will “need to be paid back at some point”.

At some point, Sunak’s image as the kindly ‘printer of endless money’ benefactor will crumble.

After coronavirus, there’ll be pressure from Number 10 to claw back the money. If so, Sunak will have to preside over a second version of austerity – and his public appeal as Mister Spendy Nice Guy will evaporate. Presumably, that would mean his credentials as the ‘Tory-Lite Politician It’s OK to Fancy’ will take a hit, too.

For now, Sunak is pretty safe, if not perfectly poised for a future in Number 10.

But if coronavirus has proven anything, it’s that anything can happen in a few months.