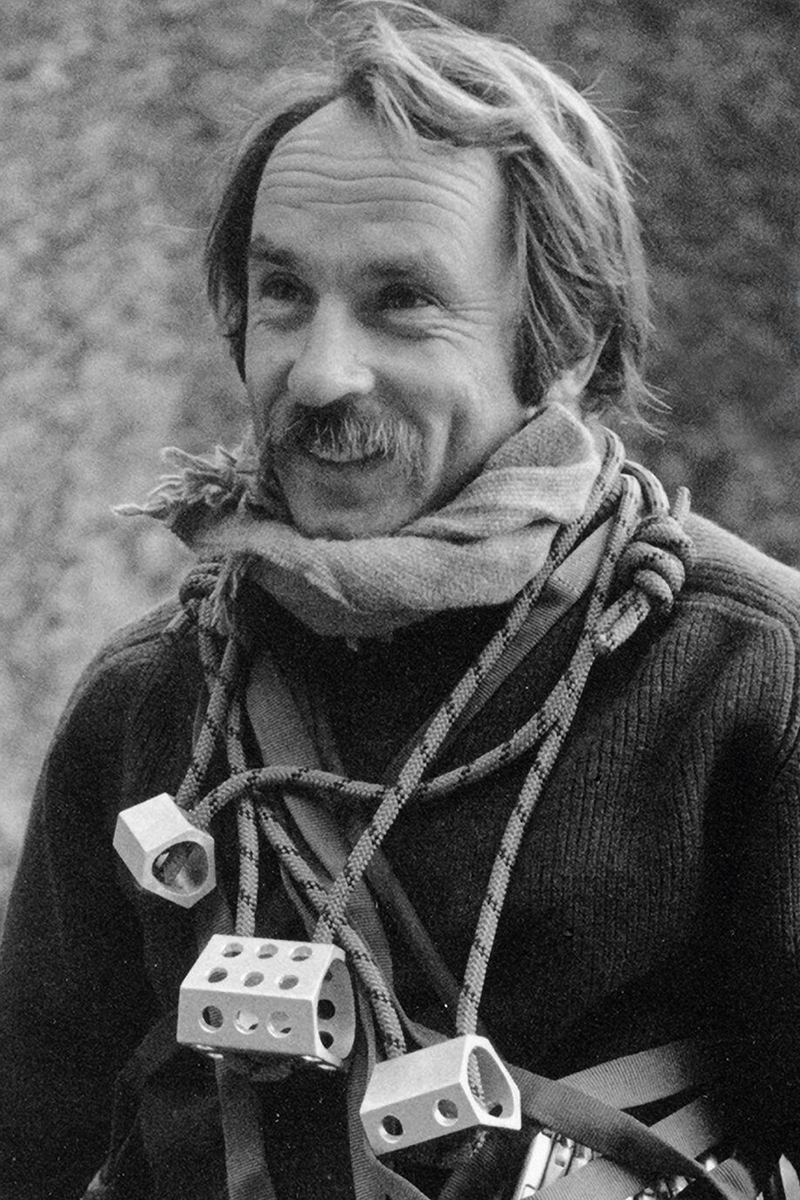

Until a month or so ago, Yvon Chouinard was not a name at the front of most people’s thoughts. In September, he made a statement regarding his business - Patagonia, a company that many people had heard of - that made almost everyone sit up. Alan Wares takes up the story of an American rock climber and surfer who has made the environment his champion.

In 2017, Forbes published its latest Rich List, and on it was a name, the owner of which was ‘very pissed off’ to see on there. Yvon Chouinard became a very successful businessman ‘by accident’. It’s a label he despises, and considers himself a failure in life for being on Forbes’ Rich List.

His mission, he had always felt, was to make the world a better and fairer place. He drives around in a slightly forlorn Subaru with a surfboard lashed on top. This man is, and has been for over 70 years, a rock climber, a surfer, a dude, a bum - not some avaricious capitalist - but also through his own sense of fairness and justice, he is a successful businessman. And he loves this planet.

Qui est Yvon Chouinard?

Yvon Chouinard was born November 9th 1938 in Lewiston, Maine in the New England area of the United States. It is known locally as ‘Little Canada’.

Chouinard’s father was a French-Canadian handyman and blacksmith. When Yvon was eight, the family moved from Lewiston to Southern California.

Chouinard has long been an environmental activist. When he was a youth, he joined The Sierra Club, an environmental organisation founded in San Francisco in the late 19th Century, now with chapters in all US states.

While still a young man, he founded the Southern California Falconry Club, and it was his investigations into falcon aeries that encouraged him to learn rock climbing. To save money, and make adaptations for the way he was climbing, a furthered his education in blacksmithing in order to make his own climbing tools. From there, he eventually started a business.

First equipment

In 1957, he bought a second-hand coal-fired forge, and used those blacksmithing skills he had originally learned from his father in making hardened steel pitons (climbing spikes) for use in rock climbing in Yosemite Valley.

He sold pitons out of the back of his car to support his surfing and rock climbing outdoor lifestyle. These pitons were a big factor in the birth of big-wall climbing from 1957 to 1960 in Yosemite. The success of his pitons led him to set up Chouinard Equipment, Ltd.

However, around 1970, he became aware that the use of steel pitons made by his company was causing significant damage to the cracks of Yosemite. As these pitons made up two-thirds of his income, he and friend Tom Frost introduced new aluminium chockstones, called ‘Hexentrics’

This committed the company to the advocacy of the new climbing tools, and led to new style called ‘clean climbing’. It revolutionised rock climbing and led to further success for the company, even though it meant the pitons, hitherto the company’s main source of income, were discontinued.

Chouinard Equipment was granted a US patent on Hexentrics in 1976, and are still manufactured by Black Diamond Equipment, a successor company to Chouinard Equipment, which filed for bankruptcy in 1989.

Patagonia

Chouinard is best known for founding the clothing and gear company Patagonia. In 1970 on a trip to Scotland, he purchased some rugby shirts and sold them with great success. He had acquired them in the first place because the collar kept the climbing sling from hurting his neck. He founded the Patagonia company in 1973, at the age of 34, and developed a wide selection of rugged technical clothing.

From the beginning, Chouinard committed the company to being a good place to work, and to be an important resource for environmental activism. In 1984, Patagonia opened an on-site cafeteria offering “healthy, mostly vegetarian food,” and started providing on-site child care.

In 1986, Chouinard committed the company to ‘tithing’ for environmental activism, committing one percent of sales or ten percent of profits, whichever is the greater. The commitment included paying employees working on local environmental projects so they could commit their efforts full-time.

While some of these human resource practices are fairly common, or even standard, across business today, this thinking was way ahead of the curve, being put into practice almost four decades ago.

The USA is not noted for its welfare to its workers in the way that many European, or even UK, employment laws operate. Two weeks is the standard annual holiday entitlement across the States, with little consideration for statutory sick pay or maternity leave, let alone the non-existent paternity leave.

Chouinard, on the other hand, through Patagonia, stated, “it would not be bound by convention” and chose to close stores and give employees paid leave from December 25th to January 2nd.” That may sound standard here, but is far from the case over there.

Since 1985, Patagonia has committed 1% of its total sales to environmental activism. In 2002, Chouinard and Craig Matthews (founder of Blue Ribbon Flies) founded ‘One Percent For The Planet’, to encourage more businesses to donate 1% of sales to environmental groups.

The company has boycotted various trade shows due to the host’s environmental and political stances. It has changed its Australian wool acquisition practices (along with fashion house Abercrombie & Fitch) on the back of some stinging criticism from animal welfare groups, who claimed the farming of the wool had been harmful to the sheep.

It responded to criticism of the sources of its goose down (from force-fed geese), used in the manufacture of clothing by ensuring it knew the source of the product, rather than relying on the supplier’s word.

In 2012, Patagonia became a certified B Corp company. B Corp is an independent, not-for-profit certification, proving a company’s environment and social credentials. Going back over recent issues of Platinum, it’s clear this recognition is something many companies in the UK are striving for.

As a major advocate of the circular economy, in 2021, Patagonia announced that it would no longer produce clothing with corporate logos added because “adding non-removable logo reduces the life span of a garment, often by a lot, for trivial reasons.”

In case you hadn’t realised, Patagonia considers itself an ‘activist company’, and has received many awards, citations and much recognition for its progressive environmental and human policies over its near 50-year history.

Future

In September 2022, at the age of 83, Yvon Chouinard announced that he was donating ownership in Patagonia to a trust to ensure profits are used for addressing climate change.

“One option was to sell Patagonia and donate all the money,” he wrote. “But we couldn’t be sure a new owner would maintain our values or keep our team of people around the world employed.

“Another path was to take the company public. What a disaster that would have been. Even public companies with good intentions are under too much pressure to create short-term gain at the expense of long-term vitality and responsibility.

“Truth be told, there were no good options available. So, we created our own.”

Chouinard’s plan

“Earth is now our only shareholder,” he wrote on his own company’s website.

“Here’s how it works: 100% of the company’s voting stock transfers to the Patagonia Purpose Trust, created to protect the company’s values; and 100% of the nonvoting stock had been given to the Holdfast Collective, a non-profit dedicated to fighting the environmental crisis and defending nature.

“The funding will come from Patagonia: Each year, the money we make after reinvesting in the business will be distributed as a dividend to help fight the crisis.

“Despite its immensity, the Earth’s resources are not infinite, and it’s clear we’ve exceeded its limits. But it’s also resilient. We can save our planet if we commit to it.”

It is estimated that profits to be donated to climate causes will amount to around $100m (£87m) a year, depending on the health of the company.

Chouinard’s stance has been met with universal praise – and some excitement – from environmental activists, many of whom are clearly hoping that other businesspeople follow Chouinard’s lead.

As for Chouinard himself, this announcement clearly means he is trying to ensure that the Patagonia brand is future-proofed, and can never fall into the hands of the companies he has accused of greenwashing.

If that doesn’t appeal to wealthy, healthy, adventure-types with a sense of environmental awareness, then little will.

Philanthropic business people

Yvon Chouinard’s donation of what could amount to $3bn for the good of the planet was like a breath of fresh air to social and environmental campaigners who have felt for years that commerce has been ignoring their pleas for them to change their ways. It has also raised questions about which business leaders might now follow on from Chouinard’s lead. A couple of suggestions…

Bill Gates

Microsoft founder Bill Gates has vowed to drop off the world’s rich lists as he made a $20bn donation to his philanthropic fund. Gates, who is thought to be worth $118bn, had pledged to give his wealth away to charity in 2010 but, somewhat perversely, his net worth has more than doubled since then.

Mark Constantine

The founder and owner of Lush, the international cosmetics firm based in Poole, Dorset has donated many millions to environmental and social causes, especially for animal welfare. The company focuses on limited packaging, and The Environment Possibility Award conferred the ‘Award of Earth Defender’ to Lush in 2020.

Jonathan Richer

In 2019, the founder of Richer Sounds, the UK hi-fi retailer, gave away 60% of his company to his 500+ employees on his 60th birthday. It meant that all staff received a £1,000 tax-free bonus for every year of service with the company. This is in addition to him donating 15% of profits to a number of charities.